Leon Battista Alberti’s Deiphira: Teaching Applications

by Francesco Ciabattoni, Georgetown University

The Deiphira Project offers teaching opportunities in several disciplines: history, paleography, material culture, philology, literature, and digital humanities. In this short essay I will propose class activities in each of the above fields as examples of the many ways one could use a this digital study of a late medieval manuscript in the teaching environment.

Introduction and Rationale

The manuscript on which this project is based is Harvard Typ 422, containing a dialogue on love by Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472). The manuscript has been dated to after 1472, the year of Leon Battista Alberti’s death because some marks and alterations written above the text have been possibly attributed to the author himself.

Before the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (ca. 1440), the only way to widely circulate a text was to make copies by hand. The printing press was imported to Italy by German typographers Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheim in 1464, but even after those expensive machines were functioning all around Europe, the practice of copying a manuscript by hand remained quite widespread for centuries. Copying a text by hand is a complex and difficult task, and copyists often make mistakes. These mistakes are sometimes quite helpful to the philologist, because through comparison and cross-examination they allow experts to establish a family tree and possibly to reconstruct an archetype, the manuscript that originated a textual tradition.

At the beginning of a course on medieval or Renaissance literature or history, American undergraduate and often even graduate students may not possess all the technical, historical and contextual information to read and understand a manuscript such as Houghton Typ 422, on which our project is based. The teacher will therefore facilitate the students in learning about the historical context of Alberti’s Deiphira.

The Deiphira project could be integrated in a project-based class Renaissance / Early Modern / Medieval studies class and is an excellent way to introduce students to digital humanities.

Learning goals include acquiring a method, familiarizing with the technical lexicon of material culture, introducing the notion of handwriting styles, observing the material (vellum in this case) of the object, and trying to get an idea of the physical manuscript in absentia of it. A good online lexicon resource help is provided on the website of the Folger Library; another one is on the University of Chicago website.

History of Alberti, Florence, and the Typ 422

Rather than simply provide historical context in a frontal class, the teacher could task the students with researching the author, Leon Battista Alberti, and his time. These could include:

- Benigni, Paola, Cardini, Roberto, and Regoliosi, Marianglea (eds.) Corpus Epistolare e documentario di Leon Battista Alberti, Polistampa, 2007.

- Cracolici, Stefano. “Flirting with the Chamaleon. Alberti on Love,” 121.1 (2006): 102-129.

- Grafton, Anthony. Leon Battista Alberti Master Builder of the Renaissance. Allen Lane, 2001

- Kircher, Timothy. “Dead Souls: Leon Battista Alberti’s Anatomy of Humanism.” MLN, Vol. 127, No. 1, Italian Issue (January 2012): 108-123

- Marcelli, Nicoletta. “Due note sulla Deiphira,” Interpres, 23 (2004): 186-193

- Najemy, John M. Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300-1550. Oxford University Press 2004.

- Najemy, John M. (ed). A History of Florence 1200–1575, Blackwell, 2006.

- Zak, Gur. “Humanism as a Way of Life: Leon Battista Alberti and the Legacy of Petrarch.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, Vol. 17, No. 2 (September 2014): 217-240.

The task should be to seek not only general information about Alberti, Florence, but also specifically about the Deiphira, and about manuscript Harvard Typ 422.

Research questions and activities could focus on:

- The historical, political, and cultural context of L. B. Alberti

- Life and works of L. B. Alberti

- Dating problems of the Deiphira as an early work of L. B. Alberti

- The debate on the nature of love in the fourteenth century (see Rinaldi)

Material Culture and Philology

Some problems about Grayson’s recensio: the manuscripts he lists do NOT include (compare this list with the list on Grayson’s edition, of Leon Battista Alberti. Opere Volgari, vol. 3 pp. 381-386) and a possible hunt for error (Grayson mistakenly cites Barberiniano Latino 4051 as Vaticano Latino 4051 on p. 383).

Students should familiarize themselves with the principles governing the page layout of a medieval manuscript. Another good resource is provided by Erik Kwakkel’s blog.

Another important aspect would be getting the students to learn about the binding of the manuscript. See, for example, this project’s reconstruction of the Typ 422 manuscript.

Paleography

Cecil Grayson published a critical edition of Alberti’s Deiphira (L.B. Alberti. Opere Volgari. Volume Terzo pp. 221-246 and 381-394). This is the only modern critical edition of Alberti’s dialogue on love. Our transcription is not a critical edition, but merely the transcription of one manuscript, Typ 422 of the Harvard Houghton library. We decided to only use Manuscript Typ 422 because it is easily accessible and represents a great opportunity for learning. Our transcription will focus solely on the text contained in that one manuscript. Manuscript descriptions can be hard to understand. To begin, students should familiarize themselves with the descriptions of medieval manuscripts, by reading other manuscripts’ descriptions and learning some conventions and technical terms.

A similar manuscript, containing Alberti’s Elementa Picturae, is Harvard Typ 422.1, also described briefly on Bond and Faye (p. 277) (click to view description).

MS Typ 422.1. Leon Battista Alberti:

Elementi di matematica.

Pap., 8 ff., 19 x 14 cm. Written by the author in Italy, ca. 1465. Bound in modern green morocco by Lloyd. Book-label of Adriana R. Salem. Deposited in 1955 by Mr. and Mrs. Ward M. Canaday.

For a manuscript with different characteristics, a great choice would be Bodleian Holkham 48, containing Dante’s Divine Comedy, but the teacher can choose any item in Italian language from one of the many libraries holding digitized collections, such as the Harvard Digitized Collection, the British Library Digitised Manuscripts, the Vatican Library, the Biblioteca Laurenziana, or the Bodleian Collection.

Back to Harvard Typ 422, the activity consists in observing the format of the description: type of script, hand, ink, mise en page (15 lines per page), decorations and illustrations if present.

Students can familiarize themselves with different handwriting styles by using a good reference text such as Clemens and Graham’s Introduction to Manuscript Studies (especially Ch- 10, pp. 135-179), or browsing one of the several quality website: such as Interactive Album of Mediaeval Palaeography.

Another important aspect of material culture regards how the folios are bound into a book. This is called Binding and can be observed here for Typ 422.

Once the students are confident and know that a description should include information about size, page design and text layout, script, stemma of the critical edition (if extant), decoration, binding, they can dedicate themselves to studying the finer details of Typ 422.

The Harvard library online catalog has this description for our manuscript (click to view description).

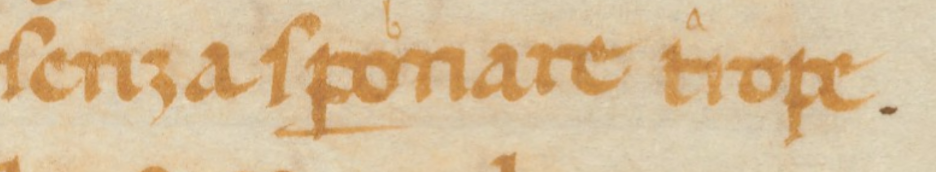

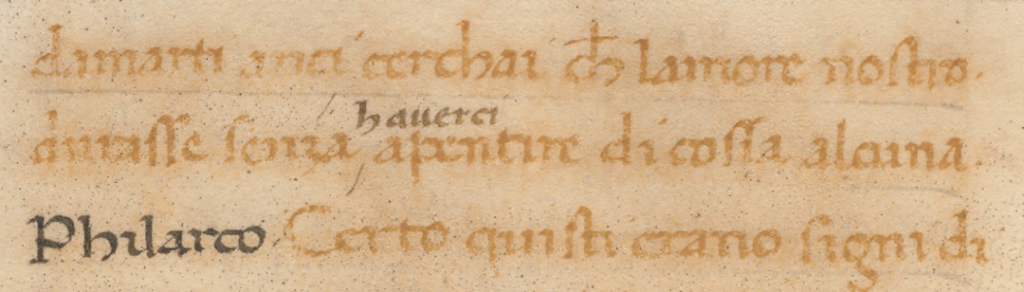

Written in a humanist script in orange ink, 15 lines per page; written area 85 x 62 mm. There are occasional alterations to the text, written above the line in darker red ink in a different hand, probably Alberti’s.

Ms H in the critical edition by C. Grayson (Bari 1974).

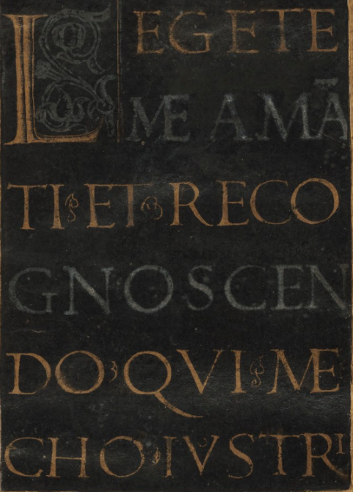

Decoration: The opening words of the prologue “Legete me amanti recognoscendo qui mecho i vostri” on f. 1 are in orange and purple letters on black, within a gold frame. Below this is illustrated a scene in which two men and a woman converse, in front of a castle in the background. There is a border of vines and flowers around the top and sides, the right edge of which was trimmed off when the leaf was detached and re-guarded.

Binding: modern full black morocco, with vellum doublures.

In a quarter green morocco and cloth tray case, 17 cm.

Also available in an electronic version.

Bond and Faye, 277.

[Image: Three figures are in a garden with a large stone structure, perhaps a wall in the background. A man and woman are seated, and robed figure stands next to them, gesturing as if in conversation.]

It has been suggested that the occasional alterations might be Alberti’s own, but this will require further investigation, as no reason is provided for that attribution. This might make an interesting investigation for further study. Where does this suggestion first appear? What is the relation of these alterations to other manuscripts of the text? Why might someone suggest a role for Alberti?

The above description contains a small mistake in the transcription of the prologue: the word “et” is missing between “amanti” and “reconognoscendo”:

The reference to “Bond and Faye” indicates the short description of Harvard Typ 422 contained on p. 277 of the catalog compiled by Bond and Faye (click to view description).

– William Henry Bond and Christopher Urdahl Faye. Supplement to the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada. Originated by C. U. Faye, continued and edited by W. H. Bond. New York- The Bibliographical Society of America, 1962.

MS Typ 422. Leon Battista Alberti:

Deiphira.

Vel., 36 n., 15 x 7 cm. 1 illuminated border with miniature. Bound in 19th c. blue morocco.

Purchased in 1956 from J. I. Davis (Hofer Fund).

After getting familiar with a manuscript descriptions, students should learn about

- Word separation

- Standard abbreviations

- Punctuation

- Page numbering systems

A helpful tool is the dynamic tour of folio 5r (thanks to Laura Morreale!)

The most part of a teaching approach to the Deiphira Project should probably be a transcription exercise. For this, some criteria must be adopted and followed, as we have laid down in our Transcription Statement ((click to view description; you may ignore the parts about html editing).

- We follow the original spelling of the manuscript, including cases in which there are evident scribal errors such as repeated or missing letters or syllables.

- In all other instances, we have carefully considered the features of this scribe’s specific habits, which include traits that can lead to some ambiguity in meaning.

- We modernize the following scribal uses: we change long s to short s (for example, santo, fol. 1r); u to v when applicable (for example, valore fol. 1r); and j to i at the beginning or end of a word (for example cittadinj, fol. 1v). Line breaks are indicated with one hard return.

- We follow the manuscript’s capitalization even in cases of a proper name (eg philarco, deiphira).

- We include original punctuation where relevant, but regularize one punctus followed by a lower case letter as a comma [,] one punctus followed by a capital letter as a full stop [.], and two vertical puncti followed by a lower-case letter as a semi-colon [;], two vertical puncti followed by a capital letter as a full stop [.]. We chose to reproduce the manuscript’s line fillers, found at the end of a line of writing with a deleted vertical bar. We also reproduce the “virgula” (a vertical bar between words) with a forward slash [/]. We chose not to introduce any diacritics, such as modern accent marks, apostrophes or hyphens in cases of elision.

- We reproduce word segmentation as found in the manuscript. We settled on this choice to avoid having to introduce punctuation and diacritics to signal linguistic phenomena marking words that are otherwise merged into scribal units in the manuscript; In some instances, we have included separation when it seemed possible, though it remained a matter of interpretation.

- Illegible text is also indicated by placing the unclear word(s) in square brackets with a question mark.

- Interlinear additions are indicated by placing the added word(s) above the written line by using the html <sup></sup> tag.

- Deleted words are marked with the <del></del> tag.

- We indicate scribal corrections with the <ins></ins> tag.

- We transcribe the marginal rubrics following the guidelines stated above. Each marginal rubric is placed next to the lines in which it appears in the manuscript and is marked by the label [marginalia:].

- We provide a brief description of the images appearing in the text. Each description is placed at the bottom of the page between brackets and is marked by [Image:].

We have expanded all abbreviations and marked them as such using italics (a macron, over an “i” for example, is rendered as “I<i>n</i>’). We based our choices on existing expanded forms found in the manuscript.

- Please refer to the Page Notes section for issues not addressed in this statement.

Coming to specifically paleographic exercises (for which students’ knowledge of the Italian language would be an important bonus), reading and transcribing from this less-than-impeccable copyist, actually proved a rather helpful challenge.

We also benefited from feedback from Prof. Francesco Furlan.

Finally, one simple and rather productive exercise is to have students individually copy the same page and then contrast and compare their transcriptions. This will expose students to reading and checking other transcribers’ work, highlighting problems and possible mistakes. Have different students transcribe the same page or pages independently and then compare the results. This should be repeated over 3-4 classes, 20 minutes each time.

Below are a few points of interest, with accompanying images, that the teacher could illustrate as a preliminary work to the transcription (click to view images).

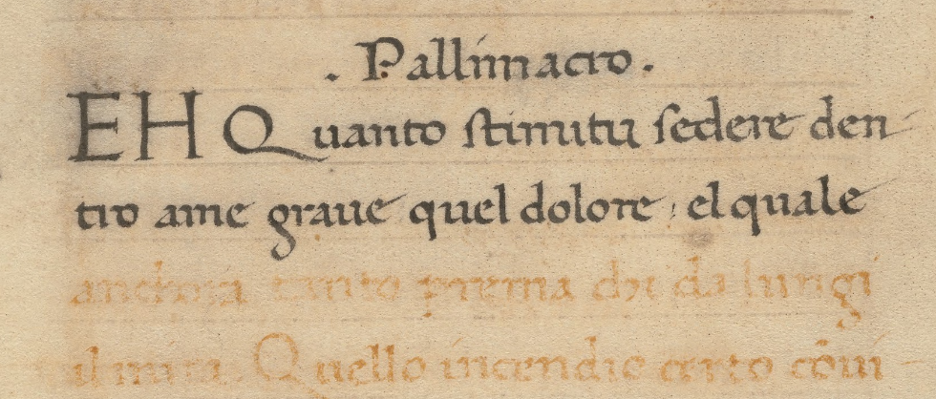

- FOL. 2r Focus on certain paleographic interpretive problems: should we transcribe words univerbate or detached (for example “stimitu”, fol. 2r) ?

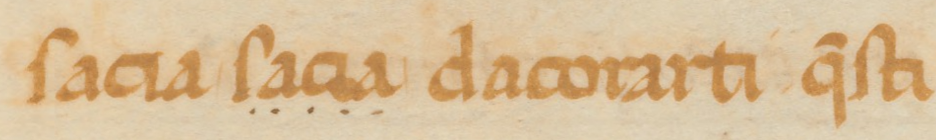

- FOL. 13r, LINE 6: Deletion of “sacia”

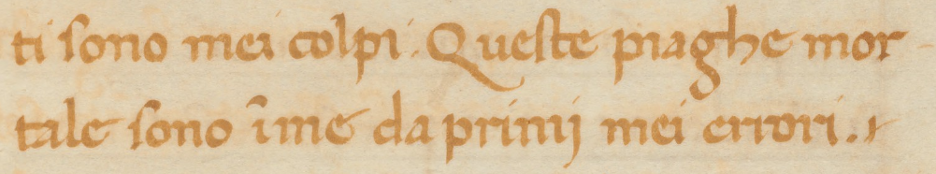

- FOL. 13r, LINES 7-8: transcribe j as i (the importance to follow the transcription statement); abbreviation: in me; filler at end of line 8

- FOL.13r, LINE 11: Scribal Intervention: switch a and b

- FOL.13v: “haverci” superscription in darker red ink, apparently in a different hand: what can it mean? According the ms description, this could be Alberti’s hand.

Websites of Interest

Bibliography

Alberti, Leon Battista. Opere Volgari. 3 vols, Bari Laterza, 1973.

Benigni, Paola, Cardini, Roberto, and Regoliosi, Marianglea (eds.) Corpus Epistolare e documentario di Leon Battista Alberti, Polistampa, 2007.

Bond, William Henry and Faye, Christopher Urdahl. Supplement to the Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada. Originated by C. U. Faye, continued and edited by W. H. Bond. New York- The Bibliographical Society of America, 1962.

Cardini, Roberto.. La rifondazione albertiana dell’elegia : Smontaggio della Deifira. Firenze, Italy: Edizioni Polistampa, 2007.

Cecere, Amalia. Deifira : Leon Battista Alberti : Analisi tematica e formale (1. ed. italiana. ed., Critica e letteratura ; 8). Naples, Liguori, 1999.

Clemens, Raymond, and Graham Timothy. Introduction to Manuscript Studies Illustrated Edition. The University of Michigan Press, 2007.

Cracolici, Stefano. “Flirting with the Chamaleon- Alberti on Love.” MLN 121 (2006): 102–129.

Cracolici, Stefano. “I percorsi divergenti del dialogo d’amore : la ‘Deifira’ di L.B. Alberti e i suoi ‘doppi’,” Albertiana, 2 (1999): 37-167.

Furlan, Francesco. “Traductions et adaptations à la veille de la Révolution. ‘Ecatonfile’, ‘Deifira’ et leurs lecteurs.” Revue Des Études Italiennes, 41.1 (1995):111-132.

Grafton, Anthony. Leon Battista Alberti Master Builder of the Renaissance. Allen Lane, 2001

Kircher, Timothy. “Dead Souls: Leon Battista Alberti’s Anatomy of Humanism.” MLN, Vol. 127, No. 1, Italian Issue (January 2012), pp. 108-123.

Marcelli, Nicoletta. “Due note sulla ‘Deifira’ di Leon Battista Alberti.” Interpres, 2004 pp. 1-18.

Najemy, John M. Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300-1550. Oxford University Press 2004.

Najemy, John M. (ed). A History of Florence 1200–1575, Blackwell, 2006.

Rinaldi, Rinaldo. “Melancholia albertiana: dalla «Deifira» al «Naufragus»,” Lettere Italiane, 37.1 (1985): 41-82.

Zak, Gur. “Humanism as a Way of Life: Leon Battista Alberti and the Legacy of Petrarch.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, Vol. 17, No. 2 (September 2014), pp. 217-240

Recommended citation:

Ciabattoni, Francesco. “Leon Battista Alberti’s Deiphira: Teaching Applications.” A Transcription and Translation of Leon Battista Alberti’s Deiphira, Houghton MS Typ. 422. Georgetown University, September 22, 2021.